|

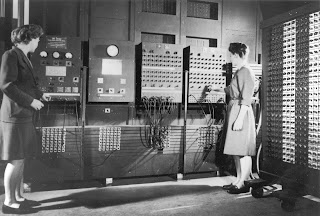

| Two women operating ENIAC; Wikipedia Commons |

In 1997, Michael Chambers and I presented “Document Coordination” for the Minnesota chapter of AIA. We discussed the roles of drawings and specifications, document quality, coordination techniques, short-form specifications, and MasterFormat 1995. Our handout included reprints of several articles about document quality; some, with scary titles, tried to prove that construction documents were atrocious and getting worse, while others how quality depended on coordination of construction documents.*

The frequency of problems in construction documents makes it easy to accept claims that they are getting worse. In 1997 I believed those claims, but I now believe the opposite. I would argue that overall, construction documents are better than ever before.

Since the presentation Michael and I made in 1997, I have continued to collect articles about the quality of construction documents. Most of the articles address current document quality, but a few discuss a change in quality. The main difference is, while the first group of articles describe specific problems, the articles that talk about changes of quality lack specificity. Rather than explain how documents have changed, they rely vague expressions of individual perception.

For example, the Construction Management Association of America (CMAA) has published several annual reports, often in conjunction with the Facility Management Institute (FMI). These reports frequently refer to a decline in the quality of documents, with conclusions based on comments obtained by surveying facility owners, but they do not include supporting information. I have seen thirteen of these reports, going back to 2000.

The reports consistently claim that quality of construction is a major concern, and sometimes say there has been a decline in the quality of documents. The 2003 survey report was the first to assert that “there is a general decline in document quality,” along with declining skill levels. There is no support for the claim, but the report does include an interesting exploration of reasons for that decline.

The 2004 survey asked, “Have you experienced a decline in the quality of design documents?” More than 70% of responders said yes. Even so, it’s worth noting that about 30% said documents at the beginning of construction were adequate or excellent.

From then until the 2010 survey, survey reports mentioned document quality only tangentially, noting that quality is always a concern, but making no specific reference to a change in quality.

|

| From FMI/CMAA Eleventh Annual Survey of Owners |

Even though about 30% of owners said document quality had declined, more than 35% said there had been no change in quality, and 25% said they were better!

While we should know of problems with construction documents, cherry-picking statistics is unnecessary and unjustified.

The most recent CMAA report, published in 2015, states, “as major challenges, the poor quality of documents tops the list.” It goes on to say, “This finding is consistent with … the 2010 study, i.e., 34 percent said the quality of design documents had declined … and 33 percent made the same claim about construction documents. … as long ago as [2005] more than 70 percent of respondents had cited a decline in the quality of design documents.” Again, the report uses only some of the information; it uses its own reports as sources but adds nothing new. The only other reference to document quality appears in a graph that shows poor document quality is an urgent challenge for owners.

One of the articles Michael Chambers and I used as a handout, “Contractor Survey Finds That Specs Don’t Measure Up,” was based on a survey conducted by Engineering News Record (ENR) and the School of Building Construction at the University of Florida.

ENR sent surveys to 500 contractors and received responses from 120 of them. Asked about the quality of specifications, 37% were rated good, 35% were rated fair, and 17% were rated poor. Compared to drawings, 85% of respondents said specifications were “sometimes or even more often” of lower quality. They reported that more than 84% of specifications “sometimes, often or generally have major omissions.” Contractors complained that specifications are boilerplate and contained irrelevant information. As was the case with the CMAA reports, the ENR survey summary expressed only subjective opinions.

How can this be?

In 1997, I accepted both claims about construction documents - that they had many errors and that they were getting worse. I had seen enough of them to know that defects were common, and because all I had heard about the change in quality was negative, I believed what I had read. In the time since then, I have noticed that every few years, the decline in construction document quality again becomes a popular topic. But, if document quality was declining twenty years ago, and has continued to decline since then, how is it that we can build facilities today that are more complex than they were in the ‘90s?

In a sense, this is the opposite of what we often seen in advertising. Every time a product is changed - and, I suspect, sometimes when it hasn’t changed - it is promoted as “New! Improved!” If laundry detergent, for example, has been improved many times since it was introduced, it should be perfect by now, but it’s not. And chances are, within the next year or two we’ll see more “improved” versions of many common products.

I contend that the quality of construction documents not only is not declining, but is, in fact, improving. Some of the improvement can be attributed to our tools. As software evolves, it makes it easier to avoid many types of mistakes. Both graphic and text processing programs now incorporate features that eliminate some problems, reduce the frequency of others, and help the user make correct choices. Also, the basic data used by computers has improved by becoming more standardized, and by being continually revised to incorporate real-world information. Many design firms have libraries of proven details and specifications that can be used as-is in many cases, and that can be easily modified to meet project-specific requirements. Building models now can incorporate complete, actual dimensions of structural elements, mechanical systems, and many products, allowing generation of more accurate dimensions, and software can analyze models to find conflicts.

I’m not saying documents are perfect. I continue to see mistakes in both drawings and specifications, and it’s likely they will never be eliminated. There will always be new employees who need to learn the correct way of creating drawings and specifications, there will always be new contractors and subcontractors who must learn how to use construction documents, and there will always be new products and processes that will challenge designer and contractor alike.

I see the problem as one of perception. Assume a typical project has 10,000 items. If 100 of them present problems, it’s likely that the 9,900 - or 99% - that were not a problem will be forgotten, and the one percent that didn’t work will be the ones that are remembered.

A word about boilerplate

As noted above, contractors and suppliers frequently complain about text that is repeated many times with little or no change. What they don't seem to understand is that some requirements do not change much from one project to another. Specifications aren't prose; they're documents that define products and processes used in construction. If a given window is used in two projects the specifications may well be identical because that particular window is required in both projects. Similarly, the general conditions may be identical in multiple projects, and even the supplementary conditions may vary only slightly from one to another.

Boilerplate isn't bad; it's necessary. However, the amount of boilerplate can be minimized by proper use of Division 01 and industry standards, and by elimination of redundancies and nonessential text.

What have you seen? Are contract documents getting worse? If you think so, please post a comment (below) to explain why, and provide evidence!

* Partial list of articles reprinted for 1997 AIA presentation: "Contractor Survey Finds That Specs Don't Measure Up,” “Contractors seek more detailed drawings, greater coordination,” “Field Interpretation and Enforcement of Specifications,” “Avoiding Liability in the Preparation of Specifications,” “Sum of the Parts: Complementary Documents,” “The Standard of Care,” “When Drawings and Specifications Conflict,” “Study pinpoints reasons for building problems.

Sheldon, you've provided some excellent points, and I will certainly have to take these into account the next time I grouse about construction documents. However, you asked for facts, and here's something to consider: When I began my career, addenda issued during bidding typically consisted of 10-20 pages of 8 1/2" x 11" sketches of partial changes to drawing sheets. Now my projects typically see 50% or more of the sheets completely reissued, some of them multiple times, as there are so many changes per page it is more efficient to simply issue the entire sheet. One could argue this is an issue of "incomplete" rather than poor quality - but the end result is the same.

ReplyDeleteI've noticed the same thing, Jori. I recall projects that had no addenda, and when addenda were needed, they were only a few pages. In the last few years, I'm embarrassed to say I have issued addenda that replaced virtually all of the drawings and the project manual. However, I attribute this not to a decline of document quality, but to a change in pace.

ReplyDeleteWhen I started my most recent job, twenty-two years ago, nearly all our projects were design-bid-build, just as they had been at previous jobs. Projects followed a fairly predictable schedule, and when the bidding documents were issued, design was complete. Today, it seems, the schedules are such that documents are issued before they are ready. A few years ago, the change in thinking became apparent; the term "bidding period" had been replaced by "addendum period." The logical result of this will be changing "construction period" to "change order period."

I'm reminded of something a speaker said at a CSI convention. He first discussed the design phases espoused by AIA - schematic design, design development, and construction documents - then went on to say that what architects really believe is that the design phase stops at substantial completion.

There is truth to this. Architects find it hard to declare that design is finished, and continue tweaking the design until construction is done. Architects also find it hard to tell owners that the time for design is done, and allow owners to continue to make changes.

With regard to the size of addenda, I think two factors need to be considered:

ReplyDeleteFirst, years ago, addenda drawings typically were 8 ½” x 11” drawings that got pasted into the set. Now, with distribution of documents via PDF, full sheets are re-issued, even if there is only a small change on the sheet.

Second, Sheldon mentioned that buildings have become much more complex. We have more systems to include and, I submit, we now tend to detail much more than in the past in response to our litigious society. I am currently working on a remodeling and addition to a large residence hall. The drawing set is over 500 sheets. The set for the construction of the original building in 1962 was a whopping 74 sheets. If you look at the size of a typical addendum in proportion to the size of the set, I suspect there has not been much change.

Steve Groth

The change to issuing complete drawing sheets and complete spec sections certainly increases the volume of addenda. Still, my recollection is that fewer changes were made in the past.

DeleteIncreasing complexity definitely has resulted in more drawings and specifications. Another factor is the ease of copying information; much of what we see in documents today is redundant simply because it's easier to copy and paste large amounts of information than to decide what truly is needed.

I like to cite a similar example in presentations. For a four-story university building built in 1905, it took 58 drawing sheets and a project manual of 51 pages. Today, hundreds of drawings and three-volume project manuals are not uncommon.

I agree that all of these things result in more documents, and more documents lead to more things to correct. However, as noted in 23 February response to a comment, I had never replaced the entire set of bidding documents until the last several years, and I did it more than once. A bigger problem, I believe, is that we now issue documents before they are complete.

The time taken in the office preparing a complete and detailed set construction documents will always be well served. I've seen many projects where crew production was inhibited due to poor cosntruction documents.

ReplyDeleteUnfortunately, project schedules make it difficult to complete design and detailing before documents are issued. Also, architects, intending to provide the best possible design, allow clients to make significant changes during the CD phase.

DeleteSheldon,

ReplyDeleteI share your opinion that construction document quality is not only not declining, but may actually be improving slightly.

My opinion is based on my forty-five years of experience as an in-house spec writer for several AE firms.

From what I’ve seen, most criticism of contract document quality comes from builders / contractors / CMs. Remember, they are hardly dispassionate observers. They just can’t seem to resist emphasizing and exploiting loopholes and other weaknesses of AE contract documents so they can justify change orders.

I can’t provide anything in the way of statistics or other “evidence” on trends in contract document quality because I’m too busy producing project manuals to gather “data” on this alleged phenomenon.

The idea that you can somehow determine a trend in construction document quality by tracking and counting the 8-1/2 by 11 pages or the number of drawings in addenda is preposterous.

In the words of Mark Twain (or maybe Benjamin Disraeli): "There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics."

The amount of paper issued in an addendum has nothing to do with the quality of the bidding documents. The addendum format, whether using brief descriptive changes, or wholesale reissueance of entire drawings or specification sections, is a matter of editorial judgement by the AE project team.

It has become common to reissue a drawing or a complete spec section for even the smallest change, so I agree that the effect of that practice on the size of an addendum is irrelevant. Using brief descriptive changes, a single paragraph could require changing every drawing sheet or every spec section, but if changes are made by reissuing drawings or specs, the same change could require replacing all drawings and specifications.

DeleteIt's worth noting that this discussion is not limited to addenda, but includes all modifications regardless of when they are made.

There's no question that construction document quality is declining in my area. This may not be true elsewhere. My personal opinion is that the Owners share as much blame for this as any other team member - but that is a subject for an entirely different blog. Suffice to say - it is absolutely true that the A/E profession is continually responsible for larger systems diversity, and more complexity - and that the reduction of fees and schedule have made their jobs almost impossible to accomplish with the necessary level of detail to build those more complex systems.

ReplyDeleteWhile you may not appreciate the use of addenda size as a way of measurement - I respond that having no factual method at all of supporting an argument is even less effective.

I also respond that our profession will continue to be fractious while builders and their opinions are addressed with less respect, as though their very profession is "less than" that of the A/E design team. My own opinion is based on having worn 5 different hats of the project team, as architect, subcontractor, manufacturer's rep, general contractor and owner's representative - and I do like to believe that it is accordingly fairly objective. The not uncommon habit of design professionals to dismiss builders as scam artists who are out to get change orders can only be based on another world than the one I exist in. In my world, change orders are always more expensive than can be adequately quantified in a change request, damaging efficiency, sequencing, quality and schedule.

As you said in your first comment, Jori, the requirement for massive addenda may 'be an issue of "incomplete" rather than poor quality - but the end result is the same.' You continued this line of thought in your 26 April comment, referring to reduced fees and shorter schedules, and again, the end result is the same. However, I still maintain that overall, documents are better now, though that certainly will vary by the location, complexity, and type of project. I don't know from experience, but I suspect that documents for developer, residential, and commodity work may not be of the same quality as those for hospitals, high-end projects, universities, and similar work.

DeleteAlthough I don't think it directly impacts document quality, your comment about the perception of design professionals is too often true. It's not universal, or, I believe, all that common, but it seems there are enough architects who feel they are superior to the unwashed laborers to taint the entire profession.

Many years ago, I visited a site with a project architect who berated a contractor for not complying with the design intent (that was a requirement of the AIA general conditions at the time). The architect's manner was embarrassing in itself, but was made even more appalling by the fact that the contractor had built what was shown on the drawings.

I readily acknowledge the value of what contractors, installers, and manufacturers know, and most architects I know are of like mind. Architects simply cannot know what contractors know about scheduling and coordination of work, what installers know about installation, or what manufacturers know about their products, and, whether they know it or not, architects expect those people to do their work properly - even if the documents are incomplete or incorrect.

In defense of architects, though, there are unscrupulous contractors who are not averse to "bidding the documents" after searching for conflicts or inconsistencies that can be exploited. The existence of books like "Contractor's Guide to Change Orders" doesn't help.

its been my experience that a really good "third party" QC review (i.e. by someone who's not intimately involved in the construction documents to date) can go a long way towards helping design documents hold up better during bidding and construction

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing such a amazing article.

ReplyDeleteconstruction drawings | as built drawings

This is such an interesting discussion! I agree that the perception of declining quality in construction documents is widespread, but as you pointed out, the data supporting these claims is often vague or anecdotal. It seems like a lot of the frustration comes from coordination issues between teams rather than the inherent quality of the documents themselves. With advancements in technology and better tools available for drafting and managing construction documentation, I’d like to believe that overall, we’re improving. But maybe the complexity of modern projects makes it feel like things are slipping through the cracks more often.

ReplyDeleteDenver Masonry